17. Autism is When...

Back on my BS

Welcome to CHAPTER SEVENTEEN of #TechnicallyAutistic: Lessons from the Periphery, where I talk about why I’ve struggled to find a place in the autistic community.

Next chapter / Previous chapter

“There’s a growing field of people with those diagnoses sharing their experiences. You might want to look into that,” said my MUSE (Mentored Undergraduate Summer Experience) mentor, Professor Hustis.

Professor Hustis, one of the chairholders in the English department, was introduced to me by my wonderful long-time advisor, Professor Pearson. I wouldn’t be where I am without Professor Pearson. I was able to start this project for MUSE because I was looking for an excuse to get out of the house and get some cash, and she thought that my article, What People Don't Realize When They Hear ‘Autism Is a Spectrum' was packed with crucial questions worthy of a full-fledged research project.

I felt a whirlwind of excitement and doubt. Sheer ambition. I already knew it. This was going to be really damn hard and even more damn rewarding.

I combed my fingers through my jet-black hair, once bleached into a neon pink and now fading from violet to a metallic mauve. I couldn’t help but think how much my world has changed since I was in high school. I’d survived a pandemic. I no longer thought twice when I told someone that I’m “bi-curious, mostly lesbian.” #ActuallyAutistic has exceeded 6 billion views on TikTok and 600k posts on Instagram, growing past its Niche Online Discourse status to becoming a hot topic in diversity and mental health. Hell, some of the internet’s hottest it-girls had come out as autistic.

And yet, my relationship with my diagnosis was just as fraught as it was eight years ago when I went to the clinic, hoping that a doctor would undiagnose me.

Earlier that year, when someone from my organization told their friend, “This is Asaka. She’s also autistic and she’s the Vice President of Breaking Down Barriers,” I recoiled. As soon as the friend left, I asked the person to please not refer to me that way. I felt a deep sense of shame. I was the head of the College’s disability advocacy org. I was supposed to be a role model. A spokesperson. An advocate. I wasn’t supposed to shy away from my autism diagnosis, unless I had another diagnosis in its place that I was trying to raise awareness for.

Executive boards, or eboard in short, are great but not without challenge. You have the annoying email tags, the endless hot potatoes, and zero work-life boundary if you live on campus. Everyone complains about their presidents and vice presidents being control freaks with sticks up their asses and more chips on their shoulders than you can count, and every incumbent thinks they can become Leslie Knope by introducing a revolutionary system or adopting a relatable and #real persona. As with most things, it’s easier said than done.

But what stumped me the most was how tricky it can be to navigate disability etiquette. I knew what it felt like to be misunderstood and cast aside, but I never knew where or how to direct my empathy because those Feminist Disability Studies readings never told me what my role was—whether I counted as autistic or allistic, or whether my inability to relate to certain stories meant I was too privileged or not privileged enough. I was perpetually flustered, never sure what was and wasn’t okay to ask or ask of somebody else.

There’s probably a rumor somewhere out there, too, that I’m a bully, that I used my position of power to make everyone hate themselves as much as I did. I would never bring other people down on purpose, but I do think that power can turn anyone into a self-absorbed clown. The weekly meetings were the only place where people eagerly awaited for me to speak and looked to me for answers, where I felt competent, so I will admit I felt a bit smug.

But nothing compared to the satisfaction of doing “hands-on” work. Even—and especially—in the most hectic moments, I delighted in the challenge of coming up with innovative solutions and creative compromises. The practice of adapting connected me to the broader disability community more than mere labels ever could. I felt like I was serving something bigger than myself, a sense of purpose countless people had promised I'd experience from speaking at panels.

“I'm autistic and proud,” so many of my colleagues would say. I could hear the strength and conviction in their voices and it was this resolve that echoed across the hollow chasms in my armor as I walked home: If it’s not the kids in middle school saying that I’m the r-word that makes me autistic, and if it’s also not the piece of paper that makes me autistic, what the hell is it that makes ME autistic?

So you’re saying that not everyone who is autistic acts A Certain Way, because autism isn’t about how the world sees you; it’s about how you see the world. But wouldn’t that mean that the opposite is also true? That not everyone who acts A Certain Way is autistic?

Despite my best efforts, my speeches and my Canva slides never conveyed the depth of my thoughts. I felt like I was circling around each idea with my hand, focusing on the silhouette rather than the dimension. But maybe I was the one who didn’t get it. For some reason, that thought made me feel a little less afraid.

“I know that neurodiversity is a broad topic; I’m specifically interested in the semantics and epistemology of diagnosis,” I told Professor Hustis. Semantics is the study of meaning, and epistemology is the study of knowledge (Epidemology is the study is disease).

“Right, so it’s like, who decides who’s autistic and what’s not? So what if someone doesn’t want to look someone in the eye? In some cultures, it’s weird to stare at people in the eye—”

“Well, I don’t know if the diagnosis applies in the first place,” I interrupted.

I tried to explain as much as I could, and I don’t know how, but I must’ve done it half-decently, because she said:

“Ah, so it’s about the scope of these categories.”

Scope. My eyes lit up.

“Again, it’s about framing, right?” Professor Hustis would say at the countless Zoom meetings in the summer session that changed my life.

Framing isn’t about whether something is true or not, but about how things are being connected with each other. The concept is also the central theme of my first reading, Pathological: The True Story of Six Misdiagnoses by Sarah Fay.

The first chapter opens with twelve-year old Fay in the emergency room, weak and clammy from under-eating. “My stomach hurt. It didn’t want food, so I stopped putting food into it,” she explains. “Not eating brought a different kind of ache (dry, but empty), but at least it wasn’t the sickening, murky pit.”

And our minds, in my opinion, are the weirdest, most beautiful, and most fucked up things to ever exist on Earth.

The vicious cycle reaches its peak during her eighth-grade field trip when she goes three days without eating and vomits when she finally tries to eat. The doctor promptly diagnose her with anorexia, a disorder typically characterized by an intense preoccupation with losing weight and restricting calories, never once asking Fay why she hadn’t been eating.

In what is one of the most brilliant passage I’ve ever read, she writes:

I didn’t know it then, but the comma was punctuating my life as an anorexic. It separated items in the list of ways I was falling apart: dry skin, brittle nails, difficulty concentrating, exhaustion. It set off information I deemed unimportant: My symptoms, which included muscle weakness and fainting, were severe. It coordinated adjectives that describe me: the thin, depressed girl. It marked an introductory phrase: Once upon a time, there was a very thin girl. It created dependent relationships: Although my family tried to help, I kept getting worse. It connected independent clauses: I got worse, and my family was worried.

That passages reminded me of AP Lang, and also of my ongoing struggle to talk about my disability in a way that makes sense to me and whoever I’m talking to. Of course, there are some major differences between the diagnoses in question. Anorexia, for one, is a horrible illness that causes a person to have upsetting, negative thoughts and hurt themselves, while autism is frequently characterized as a neurotype, or a natural difference in how someone's brain works.

Still, both diagnoses are flawed attempts to describe what’s happening inside a person’s mind. And our minds, in my opinion, are the weirdest, most beautiful, and most fucked up things to ever exist on Earth. I knew I couldn’t possibly be the only one who, despite having all the symptoms of a condition, felt disconnected from the bigger “picture” implied by a diagnosis.

In most autism infographics, features like “difficulty using nonverbal communication” and “difficulty understanding nonverbal communication” are lumped together under overarching statements about how autistic people “relate to people” or “make sense of things”, and of course, “see the world” differently from someone without the condition. When I asked some of my colleagues about how autism affected their day-to-day life, I received similarly… vague? broad? generalized? responses. A big one I got was “I have difficulty with tone,” which begs the question: do you have trouble using tone or understanding tone or both? Most, if not, all people I’ve asked told me they had some degree of difficulty understanding tone.

These narrative structures have taken on a life on its own, feeding on inference rather than explicit clarification from an “official” source like the WHO. I’m not saying that this is wrong, just that I sometimes get confused because it wasn’t what my diagnosis was based on.

My autism diagnosis has shaped the trajectory of my life, but I sometimes find it much easier to avoid the subject because it can get stressful, like a last-minute cram session where everyone compares answers with anxiety and a hint of accusation in their eyes: Wait… So… Who got it wrong?

So you’re saying that not everyone who is autistic acts A Certain Way, because autism isn’t about how the world sees you; it’s about how you see the world. But wouldn’t that mean that the opposite is also true? That not everyone who acts A Certain Way is autistic? That’s how I’ve been thinking about all this for the past few years.

My autism diagnosis has shaped the trajectory of my life, but I sometimes find it much easier to avoid the subject because it can get stressful, like a last-minute cram session where everyone compares answers with anxiety and a hint of accusation in their eyes: Wait… So… Who got it wrong?

I will admit that sometimes, the voice in my head that says “I’m not really autistic, am I?” sounds awfully like the twelve-year-old coming home from school sobbing, asking if she’s fat. She doesn’t need anyone to pinch her tummy, look through her wider friends’ tagged posts for unflattering shots, and say “Don’t be silly. You’re not fat; you’re beautiful!” as though those two things are mutually exclusive! God no! Fuck no!!! What she needs is for someone to listen to and care about what she’s feeling—lonely, angry, embarrassed, anxious—so that she’s not just stuffing them away under “I feel fat.”

When I get too stressed, I try to step back and ask myself what is it that I’m afraid of:

Being dismissed?

Being excluded?

Being treated as a liability?

Because no one deserves that, whether they’re autistic or not. No one.

NO. ONE.

But also, it’s not that simple. Securing equality for people with disabilities starts with acknowledging that disabled people are worthy and human just like anyone else, but it shouldn’t stop there. Inclusion isn’t just about being okay with a disabled person sharing your space; you have to think about what their daily life is like and the barriers they face, instead of assuming there is one standard way to do things.

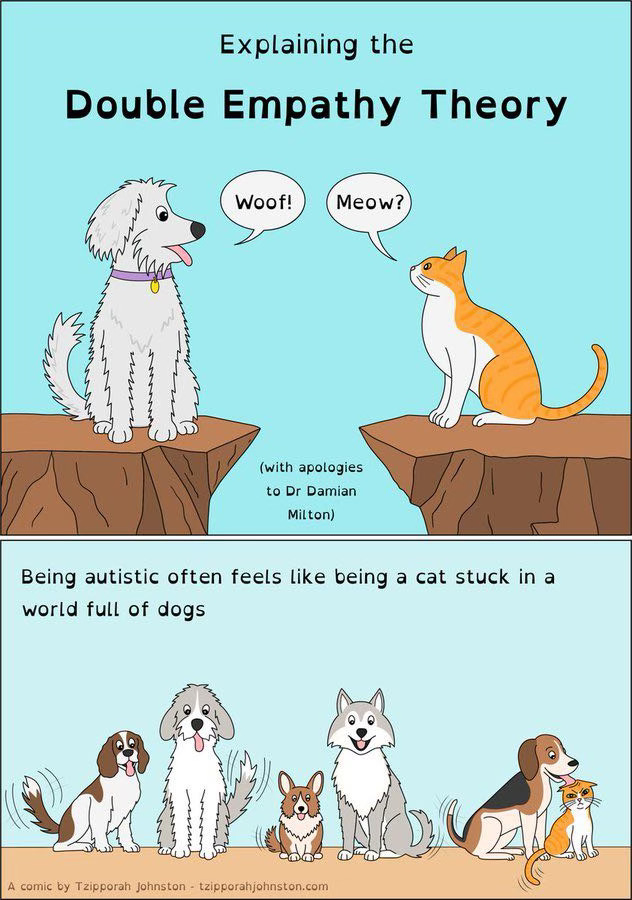

(Graphic by Tzipporah Johnson/@tzipporahfeiga)

And that’s where I run into trouble. I struggle because so much of the widely circulated "tips" for respectfully communicating with autistic people leaves me feeling disempowered and set up for failure.

In the past decades, our culture has blamed society’s abysmally low expectations for autistic people—that they are incompetent, incapable, and unable to learn—on its failure to look past differences. But today, advocates are asking a very good question: what if the real problem is our culture’s failure to acknowledge difference?

I struggle because so much of the widely circulated "tips" for respectfully communicating with autistic people leaves me feeling disempowered and set up for failure.

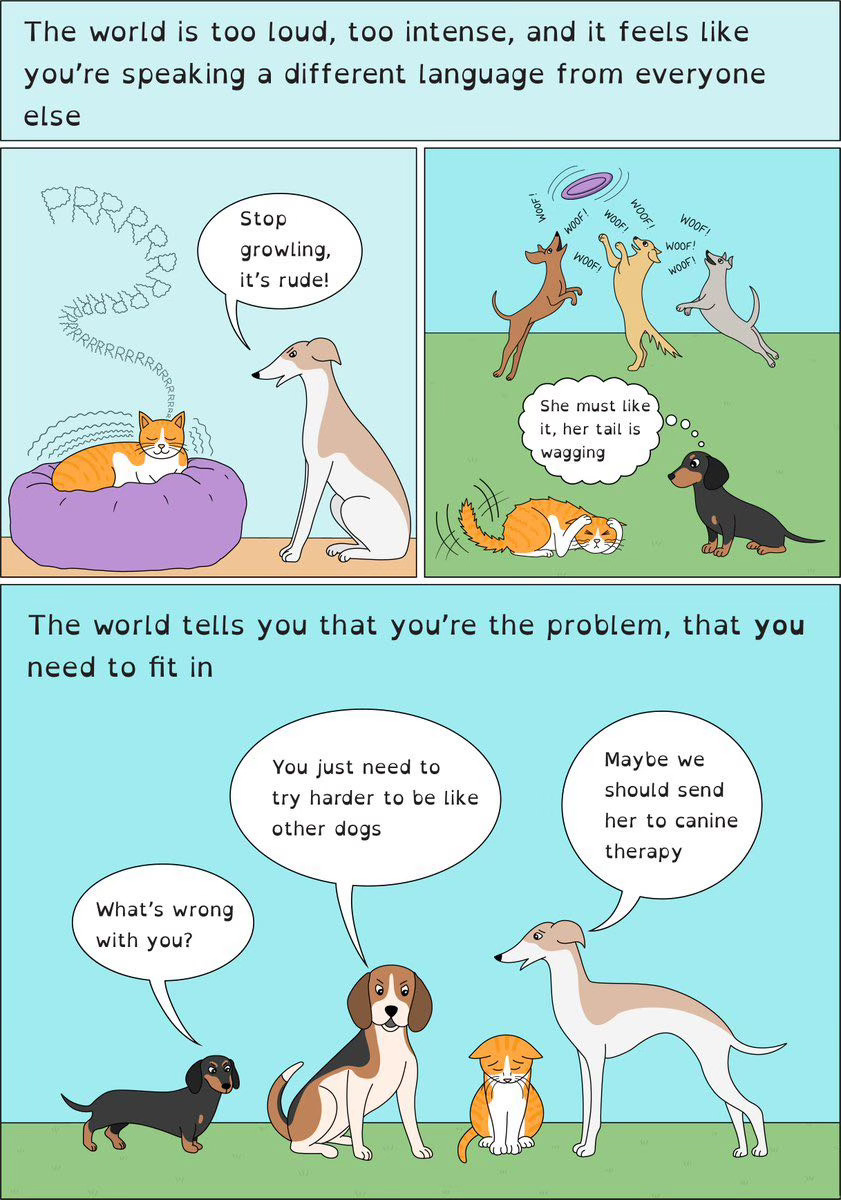

Though people have been saying for years that autism isn’t synonymous with a lack of empathy or intelligence, I’ve talked to so many non-autistic people who, after a negative experience with an autistic friend or coworker, fall back to resignation: they make me feel bad, but I’ll allow it because they’re not as good with people/feelings. Usually, it turns out that there was a communication breakdown neither party was aware of, and I think advocates on social media have done an amazing job of illustrating where communication can go awry between autistic and non-autistic folks.

(Graphic by H.J. Richardson/@hat.taks.uk)

I suspect that the delicate balance between being mindful of someone’s needs and treating them differently is something we, as a collective, will continue to grapple with for years to come. But when I think about where my own needs fit into this conversation, I face a sense of uncertainty that I feel far more alone in.

Promoting the view that autistic people have a different, not less, way of communicating, means that we have to stop using “autism” as a catch-all diagnosis given to everyone who struggles socially, let alone as some miscellaneous loony bin for anyone who’s really fucking weird, and start talking about what these differences are. I’m not sure what that means for me. I know how I communicate, and I don’t see myself fitting into any of the pre-determined roles championed by the autistic community.

Promoting the view that autistic people have a different, not less, way of communicating, means that we have to stop using “autism” as a catch-all diagnosis given to everyone who struggles socially, let alone as some miscellaneous loony bin for anyone who’s really fucking weird, and start talking about what these differences are.

When I first started following #ActuallyAutistic around 2016, I remember seeing everyone get really angry every time a new TV show or movie with an autistic character was announced. Now, I hear less of that frustration. It seems like the industry is finally listening and hiring more informed people to portray autistic people in a more respectful and accurate manner.

I haven’t started watching TVs and movies yet (though I hope to do that very soon), but I follow updates on social media. I see that today’s autistic characters are increasingly diverse, especially in terms of race, gender, and sexual orientation. Writers are making more of an effort to integrate autism into universal themes and broader social dynamics. Autistic kids can see relatable role models, not just a stick figure with symptoms pasted from WebMd that performs solitary activities, or alternately, Buddy-Hobbs-level shenanigans. I also see that much of the “positive representation” we see today are essentially a more polished version of a decades-old trope: the autistic character says and does things that others find baffling, but there’s always a reason. Their rationale is fair, logical, and endearing if not enlightening.

One example is Extraordinary Attorney Woo, a K-drama about Young-Woo, an autistic rookie attorney determined to forge her path at a Seoul law firm, despite other people doubting her. In one scene, Young-Woo’s colleague, Su-Yeon, calls Young-Woo before an important meeting to bring "any” pair of pants, and Young-Woo arrives with pink pajama pants. Su-Yeon gets flustered because the pants don’t match her professional outfit. But Young-Woo had taken the request literally and thought Su-Yeon wanted something comfortable.

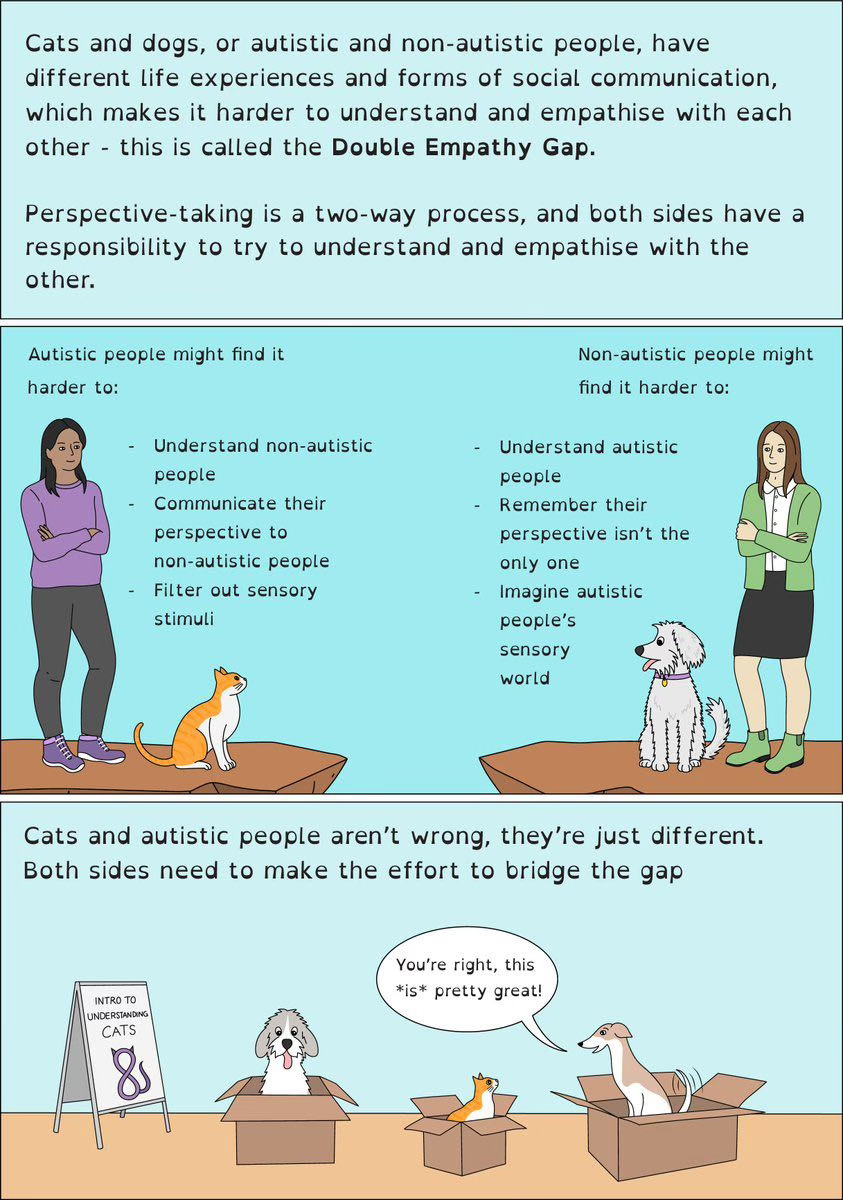

(Graphic via Autistic Not Weird/autisticnotweird.com)

As someone whose strongest connection to autism comes from how society perceives and treats me, rather than an internal sense of how my brain works, I’m grateful yet frustrated by the growing fascination with the big why. Why am I like this? I’ve always wanted to talk about it, but I worry whether anyone would understand, or believe me.

If it’s not the kids in middle school saying that I’m the r-word that makes me autistic, and if it’s also not the piece of paper that makes me autistic, what the hell is it that makes ME autistic?

When I was first diagnosed at ten, my social differences were far from superficial. I was just as different in my thinking as I was in my behavior, which is to say very. A lot of what other kids considered a big deal, I didn’t think was important, and vice versa. I just couldn’t relate. However, I’m not sure if that points towards autism, or something else entirely.

Some of the wisest people I know are autistic. Many of them have intensely focused interests, don’t care for small talk, and thrive on rules and certainty. Sometimes I don‘t know what to say because they never outgrew these traits, and I did. I know that for so many people, these features are intrinsic parts of their identity that they nearly killed themselves trying to hide or fix; for me, they are relics of an irrevocably good but developmentally fraught childhood, marked by phobias, dissociation, and learning setbacks owing to extensive lapses in attention, and a near inability to hear my own thoughts unless I was writing or talking.

In these conversations, distancing myself from my diagnosis has felt like a protective measure. I worried that if I removed the shield of “It’s not the same,” then we’re going to go down the “Oh, I get it; I used to be like that but thank God I’m not anymore.” Then, someone would get hurt.

I mean, it really is not the same. The last time I struggled in the ways they have, I lacked emotional permanence and basic abstract thinking skills. The people that I talk to possess far more (relative) insight than my five-, nine-, or twelve-year-old self could ever imagine. They’re the therapist friends. The peacemakers. The philosophers.

Speaking of philosophers…. Why do I overthink this? The bottom line is, I know and respect autistic people. So why would sharing a diagnosis—and a broad one at that— with them be such a scary thing?

Next chapter:

Previous chapter: