Hi friends! This is CHAPTER ONE of #TechnicallyAutistic: Dispatches from the Periphery, a micro-memoir about words, meanings, and the dilemma of diagnosis. If you’re new, start HERE.

AUTISM SPECTRUM DISORDER.

Etched in my medical records and written on my forehead, these three words mean everything and nothing at the same time. For more than half of my life, my diagnosis mediated my interaction with the world.

I was nine when I was diagnosed with autism. I’m twenty-two now, which means that I spent more years with it than without. Anyone who’s talked to me within the past few years knows that my relationship with my diagnosis is… complicated, to say the least.

Before I recount our messy history, I want to make it clear that diagnosis and disability are not interchangeable for me. Disability can refer to all flavors of mental or physical states that affect a person’s life. The rest is up to interpretation. Every time I talk about my disability, I get to determine which parts of my life I’m referring to (and which parts of my life I’m not referring to), and what my opinions on it are. Diagnoses, on the other hand, are the names we attach to the said state to further classify them.

This is important. If someone says that they’re struggling with their autism, you could take that as them saying they’re struggling with the parts of themselves that are known as autism. This is not what I mean when I say that I’m struggling to accept my autism diagnosis. What I mean is that I’m struggling with society’s categorization of these parts, as opposed to the parts themselves (that definitely happens, but that’s not the point).

Autism isn’t the only diagnosis I’ve received. I have been diagnosed with ADHD, and in many conversations, “my ADHD” serves as a crucial reference point. I may not exhibit every single trait associated with ADHD, but I can still relate to the overarching themes and say, “It’s the same general idea, you know?” That’s good enough for me. The connection might not be immediately obvious, but once I point it out, people tell me it makes sense.

I cannot say the same about autism. I’ve looked left and right for descriptions of autism I could relate to, and I haven’t had any luck. In recent years, structuring my self-advocacy around the concept of autism has left me feeling confused and burnt out.

It’s been that way for a long time. But not always. What can I say? It’s complicated would be an understatement of the year.

When I was very little, I was one of those textbook cases.

My mom knew there was something different about me as early as the age of four. If kindergartens had class superlatives, I’d be voted most likely to get lost during field trips. If I went too long without being directly spoken to, I became distracted. Well, distracted is also an understatement. I retreated into my own world, a kaleidoscope of books, animals, plants, and some more books.

I was a precocious reader. Until third grade, I went to a Japanese school. At just five years old, I was reading Kanjis, or Chinese characters. At playdates, I’d ditch my friends to rummage the house for books. Then, I’d barge into the kitchen to talk to the moms about what I just read.

In first grade, I was already reading at fourth- and fifth-grade levels. In all other departments, I continued to lag behind. I couldn’t finish a worksheet or organize the contents of my backpack without her watching over my shoulders. When left to my own devices, I’d lose my train of thought, and she’d walk into my room thirty minutes later, realizing the mistake she made when she left me unsupervised (No actual devices, thankfully. I don’t want to think about what would’ve happened if I had access to iPads and DS).

Doing my homework was half the battle; the other half was getting it to the teacher. I was always the last one to turn in my assignments. I was too busy playing with my eraser, doodling, and thumbing through my textbooks that I wouldn’t notice my classmates walking across the classroom to submit their work.

I never had strong motor skills. Every time I saw a ball moving in my direction, I flinched. My teacher reminded me that the rules of dodgeball did not apply to soccer or basketball. That I knew, but every time I tried to play correctly, a slapstick sequence ensued. There was a thud, a crash, and aah, aah, aah... Those who spent enough time with me recognized my distress call (Once, a kid said that my name was Aah-saka — get it?).

Despite the occasional teasing, my classmates tried to understand. But I wasn’t in the same headspace. A poster child of the expression, I do not wish to be perceived without my consent, I spoke in periods never exclamations, rarely looked people in the eyes, and kept my friends away from my bilingual family.

My parents scratched their heads. Unlike other people who had social anxiety, I had little regard for social norms. When someone complimented me, asked me if I was okay, or recognized me in public, I didn’t smile. Instead, I would run and hide. Once, I lashed out at my mom’s friend, flinging my stuffed labrador-greyhound mix, Snow, at her at the checkout line, because she ran over to say hi.

My parents signed me up for weekly counseling with a therapist in New York City. They also had someone else come to my school to give me a psychological evaluation. The unfamiliar woman pulled me out of class, asked me about my family, and made me solve a bunch of puzzles. That woman, a learning specialist, became the first person to give me a tentative diagnosis: Asperger's syndrome, an outdated term for autism without speech delays or intellectual disability.

“Well, she said that she’s almost certain you have Asperger’s, but that we had to follow up with a specialist to confirm,” my mom recounted.

To my mother, pursuing a formal diagnosis was like beating a dead horse. The most valuable takeaway, for her, wasn’t the quasi-diagnosis. The most valuable takeaway was the thorough analysis of my learning style that accompanied my IQ scores. The report stated, for example, that I had a very hard time pairing letters with shapes, while I aced the vocabulary portion (It also noted that my attention span was shorter than what is expected for my age, though that was hardly a surprise).

“It didn’t matter to me what it was called. What mattered to me was that you got what you needed,” she told me.

In third grade, my psychosocial development reached a critical point.

Once I entered the public school system, things changed. When my parents transferred me, they informed the receptionist about my suspected disability and asked her about my options. She told them to go talk to the Child Study Team.

The Child Study Team told my parents that they would have to gather more information — including proof of diagnosis (the psychological evaluation from the prior year wasn’t enough) — in order to determine my eligibility for special education services. Then, they could talk about options.

To my parents’ relief, the transition went smoothly. I was too excited to meet new people and start a new life to feel sad about leaving my old school. The teachers said that my English was excellent.

The first few months of third grade consisted of watchful waiting. The folks from the Child Study Team frequently visited the classroom with a clipboard in hand, though I highly doubt it was all for me. Rumor had it that my class, 3N, was the worst behaved, and that the teacher, Ms. Nally, was stretched thin.

Ms. Nally always had this welcoming aura. Even after the contractors installed the Smartboards, she would huddle us on the carpet to read us books. Once, she read us a book called The Junkyard Wonders. The story begins with the author, Patricia Polacco (Trisha), horrified to find out she has been enrolled in a class known as “the junkyard.” The kids in the class are written off by the rest of the school because they have all sorts of “issues.” But soon enough, Trisha learns the truth about her classmates: a determined group of students, each brimming with triumph and talent.

I introduced Ms. Nally to my microcosm of Snow and her friends, my iffy home life, and my particularities, or feeling problems, as I would call them. Being noticed still triggered my fight or flight response, and these instances became more frequent, now that I was going to school with all the kids in my neighborhood. Getting a Shiba Inu during Thanksgiving also unleashed the control freak in me. I had a how-to-book for training dogs that I really liked, and I became indignant when my family didn’t do exactly as the book said. Shiba Inus are finicky, but so was I. It also bothered me when the stations in the living room weren’t arranged a certain way. Ms. Nally never judged. She told me that what I was feeling was okay.

Ms. Nally introduced me to her colleagues. One of them was Ms. Martin, a brunette who always carried a brightly colored iced coffee cup and showed me pictures of her toy poodle, Mocha. One day, Ms. Nally instructed me to meet Ms. Martin downstairs for Reading and Writing, instead of staying with her. She told me that I was a writer destined for greatness and that Ms. Martin was going to help me.

Ms. Martin’s classroom was a special education classroom. I didn’t know this at the time, but I was allowed in there because my parents now had my diagnosis on paper. Or two. One doctor had declared that I had ADHD; another declared that no, I had Asperger’s (believe it or not, clinicians were advised at the time that autism and ADHD were mutually exclusive). My parents were looking for a third opinion.

Was it a form of autism, or ADHD? Should I be on Ritalin? Was I getting enough help at school, or did I need something more?

Before third grade ended, my parents sat me down to tell me that they found the answer, at last: I had autism.

Two weeks before summer break, my parents made their final stop: a neurologist’s office in the City. The appointment didn’t go as expected. While my mom was speaking to the doctor, she talked about transferring me to yet another school, not realizing that the walls were thin and I heard her.

I flung open the doors, sobbing. What do you mean, a different school? Why didn’t you tell me? HOW COULD YOU DO THIS TO ME?

My parents explained to me that the special education program at the other school had more resources to help me. What they told me blurs into the conversations I had with multiple adults in my life, over the next days, weeks, and months:

Grown-up: You know how you said you’re sensitive? Things that don’t bother most people might bother you.

Ten-year-old me: Yeah?

Grown-up: That’s because you have autism.

Ten-year-old me: Okay.

(Once, when I was still at the Japanese school, I came across a passage in a children’s encyclopedia that said people with autism “reacted to things differently.” I asked my teacher if I had autism. “That’s a good question. I’m not sure,” she replied. My mom also said she wasn’t sure. Ultimately, I didn’t think much of it.)

Grown-up: That also explains why getting along with people hasn’t been easy for you. You might have trouble understanding certain things, so it can be harder for you to make friends.

Ten-year-old me: Oh, I don’t have trouble understanding anything. I think other people have trouble understanding me, though. But that’s because the things that don’t bother other people bother me, like you said. And you’re saying that’s autism, right?

Grown-up: That’s right, kiddo.

Ten-year-old me: Okay! That makes sense!

As far as I was concerned, my life was otherwise ordinary. I viewed my being different as being confined to a few trigger points. I thought that as long as nobody upset me, I wouldn’t be disabled. My early understanding of my brain didn’t account for my social and academic needs, or the reason my emotions ran my life in the first place: I didn’t have a cohesive internal dialogue.

My thoughts were going so fast in so many different directions that nothing registered. When I first I saw one of those “thoughts, feelings and behaviors” triangles, I didn’t get it. The idea, of course, is that by thinking about things a bit differently, I can make myself feel better. But I didn’t think; I just felt. To me, there was no difference between emotional pain and physical pain: they were uncontrollable, unchangeable, and usually blame-able to some external force, whether it be the scrape of concrete or the peering gaze of a classmate. “Positive self-talk” stuck as well as a wet band-aid.

Since I couldn’t hear my own thoughts, I expressed opinions by working backwards, pulling cliches and platitudes from books that struck a resonant chord and letting the echos finish my sentences. This resulted in an over-simplified, almost cartoonish view of people, things, and situations, that I used to reinforce my conviction that I was always right.

The truth was, half of the time, I had no clue whether I was feeling anxious or hurt or frustrated. I opted for dramatic language, like traumatized and depressed (Just wait till… never mind). The thing about self-awareness, of course, is that you don’t know what you don’t know.

Looking back, it’s also clear that I didn’t have the emotional permanence that I have now. As a kid, I found it hard to imagining how my feelings about things might change over time, or what other people were thinking I wasn’t there. As an adult, I’m the one telling people to look at the big picture. The only “out of mind, out of sight” moments I have are with my emails. I can only imagine what it would be like to navigate the world like this today. But I do remember that things were different before. I must’ve known at some basic level that feelings were not permanent and that people had their own lives, but I couldn’t quite form a compelling story in my mind that could take my mind off of whatever I felt like doing in the moment. I always needed a lot of convincing.

After I bid my farewells to 3N, I told my parents that I was suffering.

“We don’t want you to suffer. But you might feel differently, once you start going there” said my dad.

Tears rolled down my eyes.

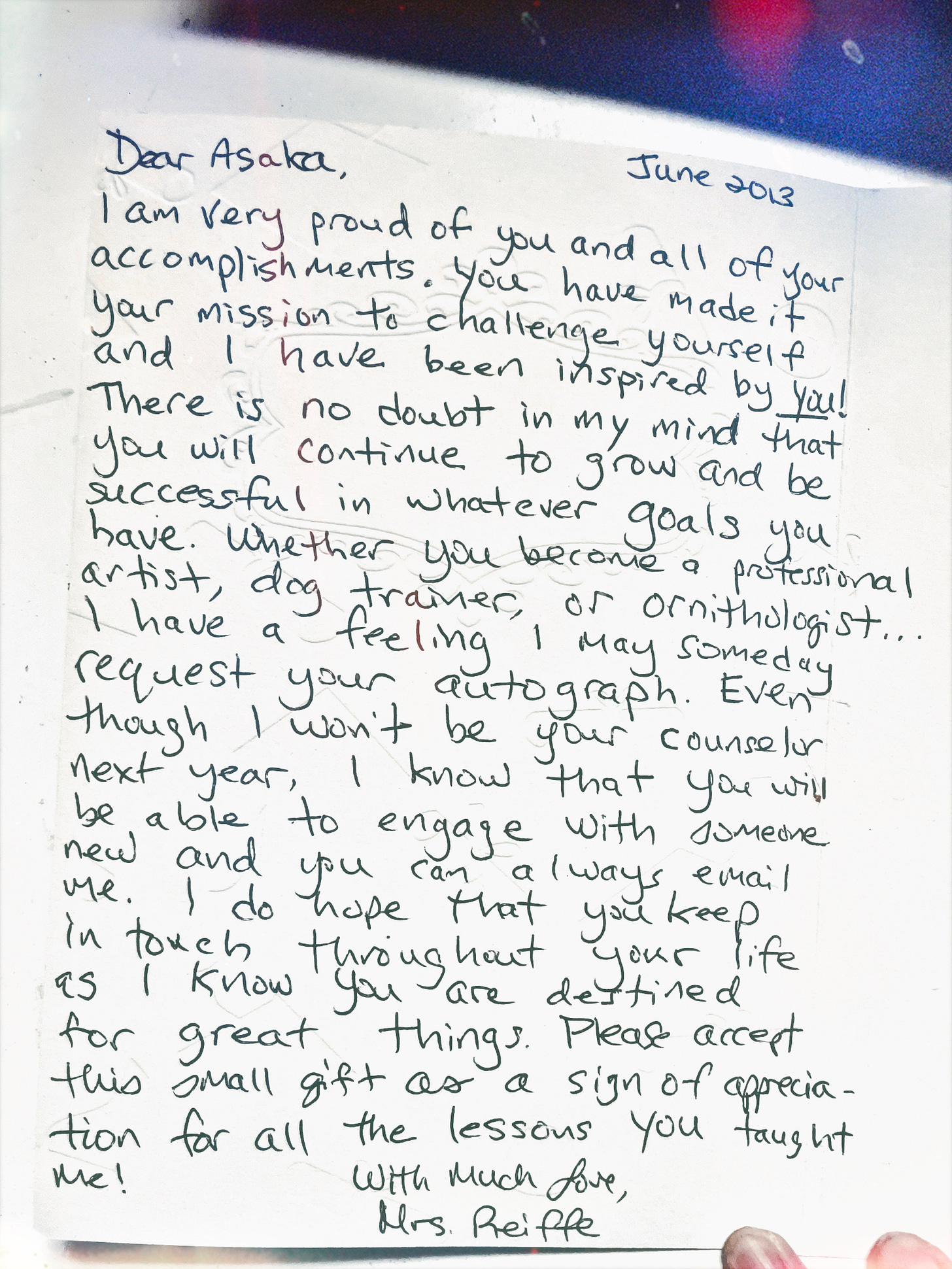

My mom wrapped her arms around my shoulder. “I know it’s hard, but think of all the good things that could happen. Remember how Mrs. Reiffe said that she knew some kids who know what you’re going through?”

There was relief in her voice. My mom has always been an encouraging presence in my life, but the diagnosis seemed to renew her sense of optimism.

I promised my parents that I’d give it a try.

The diagnosis afforded me a safety net while I learned and grew.

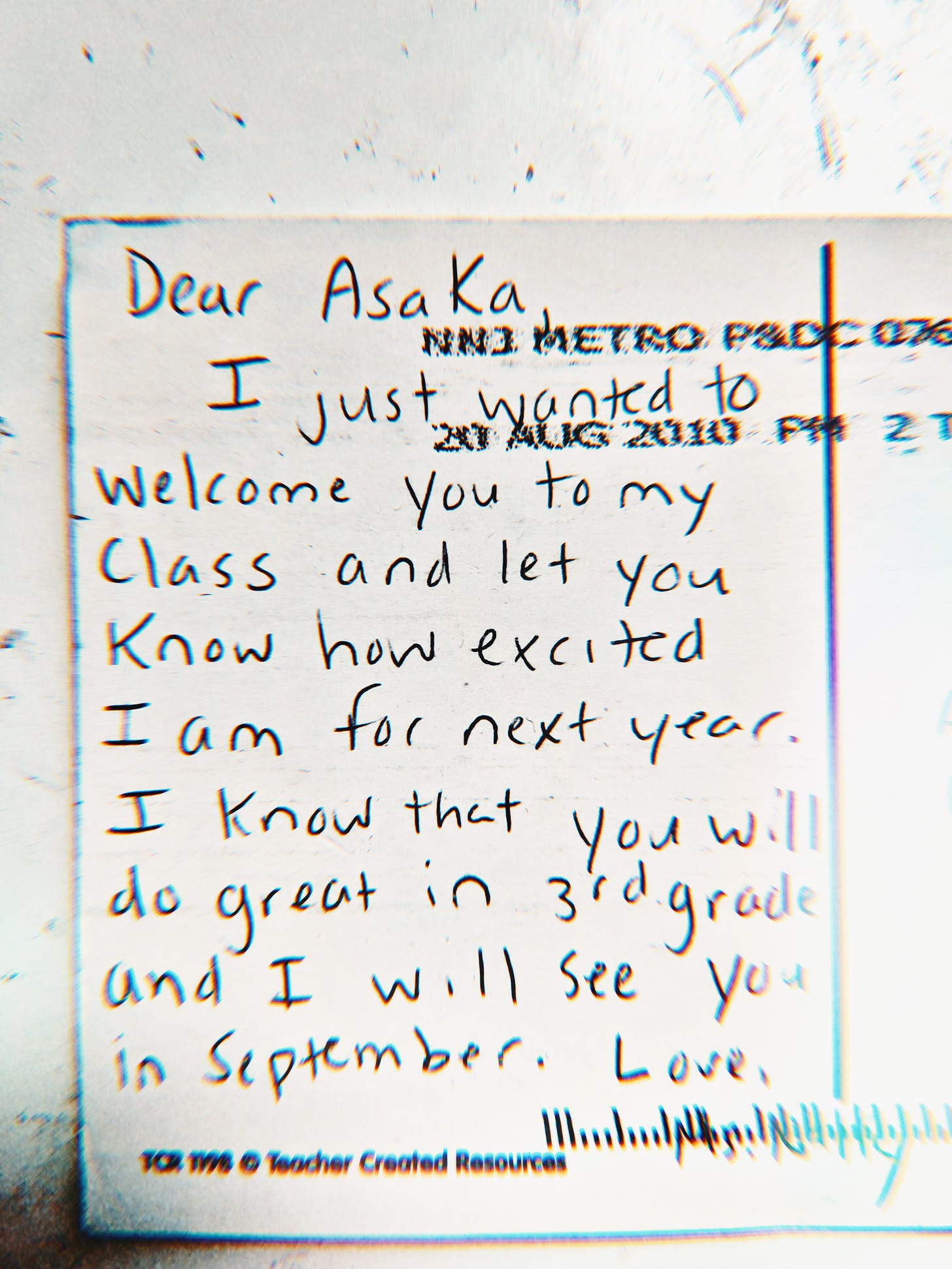

Mrs. Reiffe was one of the school counselors Ms. Nally introduced me to. Mrs. Reiffe (Reiffe, like a coral reef, she said. Weef, I said, since I couldn’t pronounce my R’s) spent her working hours driving back and forth between multiple schools in our small town. She also saw what Ms. Nally saw in me, that I didn’t see at the time: I was a writer. Since the new school was under the same district, I would continue working with her.

The new school wasn’t that bad. My parents told me that if I was still suffering at my new school, we could talk about switching back. Though I had my ups and downs, switching back never crossed my mind.

My first challenge at the new school was navigating the attention directed at my upbringing (Where are you from? When did you move from Japan? Oh, I didn’t know you went to Bryan! Wait, you’re Japanese? Park is a Korean name, right?). It took everything in me not to crawl under a desk. Mrs. Reiffe said that perhaps, I could give a presentation at homeroom to talk about my background.

When we met to brainstorm, I listed off the key points: My dad is Korean, but my mom is Japanese. I can only speak Japanese and English, and no, I never lived in Japan. Until third grade I went to a Japanese school — that is, a private school near Fort Lee, not a school in Japan. I only went to Edward H. Bryan School, the other public school, for a year… And I must’ve mentioned something about me being unique and sensitive because she said it would be very helpful if I could fill my classmates in on the whole autism thing.

I was impartial to the idea. Mrs. Reiffe also thought it was a good idea to link a Brainpop video on autism. I thought that was pointless because the subject of the presentation was me, not autism. But long as I could talk about my upbringing, and rip out that band-aid, I was happy. I thought, why not?

The presentation went well, and Mrs. Reiffe continued to encourage me to write. She always brought pen and paper to our weekly check-ins. When the iPads came in, she made sure to rent one so that I can use the Notes app. It was still hard to hear myself think, but I could at least see myself think.

Thank you for reading PART ONE of my micro-memoir, #TechnicallyAutistic: Dispatches from the Periphery. Click HERE to learn more, and subscribe (it’s free!) for live updates.

Until next time,

— Asaka